LRU is one of the most widely used cache eviction algorithms that span its utility across multiple database systems. Although popular, it suffers from a bunch of limitations especially when it is used for managing caches in disk-backed databases like MySQL and Postgres.

In this essay, we take a detailed look into the sub-optimality of LRU and how one of its variants called 2Q addresses and improves upon it. 2Q algorithm was first introduced in the paper - 2Q: A low overhead high-performance buffer management replacement algorithm by Theodore Johnson and Dennis Shasha.

LRU

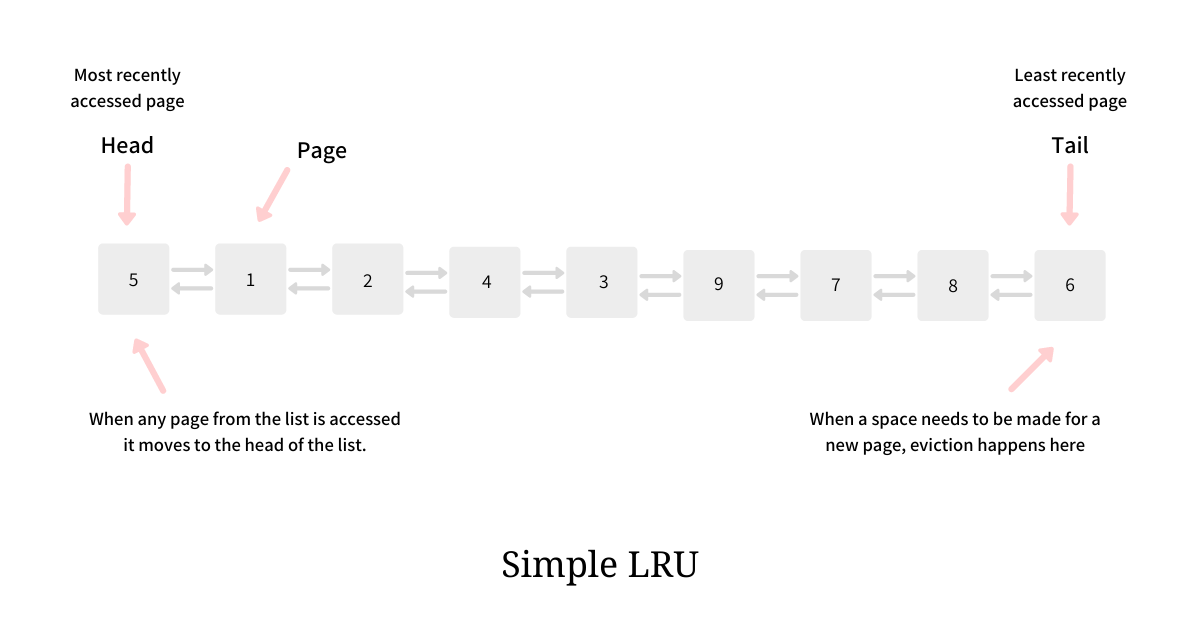

The LRU eviction algorithm evicts the page from the buffer which has not been accessed for the longest. LRU is typically implemented using a Doubly Linked List and a Hash Table. The intuition of this algorithm is so strong and implementation is so simple that until the early ’80s, LRU was the algorithm of choice in nearly all the systems. But as stated above, there are certain situations where LRU performs sub-optimal.

Sub-optimality during DB scans

If the database table is bigger than the LRU cache, the DB process, upon scanning the table will wipe out the entire LRU cache and fill it with the pages from just one scanned table. If these pages are not referenced again, this is a total loss and the performance of the database takes a massive hit. The performance will pickup once these pages are evicted from the cache and other pages make an entry.

Sub-optimality in evictions

LRU algorithm works with a single dimension - recency - as it removes the pages from the buffer on the basis of recent accesses. Since it does not really consider any other factor, it can actually evict a warmer page and replace it with a colder one - a page that could and would be accessed just once.

2Q Algorithm

2Q addresses the above-illustrated issues by introducing parallel buffers and supporting queues. Instead of considering just recency as a factor, 2Q also considers access frequency while making the decision to ensure the page that is really warm gets a place in the LRU cache. It admits only hot pages to the main buffer and tests every page for a second reference.

The golden rule that 2Q is based on is - Just because a page is accessed once does not entitle it to stay in the buffer. Instead, it should be decided if it is accessed again then only keep it in the buffer.

Below we take a detailed look into two versions of the 2Q algorithm - simplified and improved.

Simplified 2Q

Simplified 2Q algorithm works with two buffers: the primary LRU buffer - Am and a secondary FIFO buffer - A1. New faulted pages first go to the secondary buffer A1 and then when the page is referenced again, it moves to the primary LRU buffer Am. This ensures that the page that moves to the primary LRU buffer is hot and indeed requires to be cached.

If the page residing in A1 is never referenced again, it eventually gets discarded, implying the page was indeed cold and did not deserve to be cached. Thus this simplified 2Q provides protection against the two listed sub-optimality of the simple LRU scheme by adding a secondary buffer and testing pages for a second reference. The pseudocode for the Simplified 2Q algorithm is as follows:

def access_page(X: page):

# if the page already exists in the LRU cache

# in buffer Am

if X in Am:

Am.move_front(X)

# if the page exists in secondary storage

# and not it gets access.

# since the page is accessed again, indicating interest

# and long-term need, move it to Am.

elif X in A1:

A1.remove(X)

Am.add_front(X)

# page X is accessed for the first time

else:

# if A1 is full then free a slot.

if A1.is_full():

A1.pop()

# add X to the front of the FIFO A1 queue

A1.add_front(X)Tuning Simplified 2Q buffer is difficult - if the maximum size of A1 is too small, the test for hotness becomes too strong and if it is too large then due to memory constraint Am will get relatively smaller memory making the primary LRU cache smaller, eventually degrading the database performance.

The full version 2Q algorithm remediates this limitation and eliminates tuning to a massive extent without taking any hit in performance.

2Q Full Version

Although Simplified 2Q algorithm does a decent job there is still scope of improvement when it comes to handling common database access pattern, that suggests, a page generally receives a lot of references for a short period of time and then no reference for a long time. If a page truly needs to be cached then after it receives a lot (not just one) of references in a short span it continues to receive references and hits on regular intervals.

To handle this common database access pattern, the 2Q algorithm splits the secondary buffer A1 into two buffers A1-In and A1-Out, where the new element always enters A1-In and continues to stay in A1-In till it gets accesses ensuring that the most recent first accesses happen in the memory.

Once the page gets old, it gets thrown off the memory but its disk reference is stored in the A1-Out buffer. If the page, whose reference is, residing in A1-Out is accessed again the page is promoted to Am LRU implying it indeed is a hot page that will be accessed again and hence required to be cached.

The Am buffer continues to be the usual LRU which means when any page residing in Am is accessed it is moved to the head and when a page is needed to be discarded the eviction happens from the tail end.

2Q in Postgres

Postgres uses 2Q as its cache management algorithm due to patent issues with IBM. Postgres used to have ARC as its caching algorithm but with IBM getting a patent over it, Postgres moved to 2Q. Postgres also claims that the performance of 2Q is similar to ARC.